Finding Your African American Ancestors

by Kenyatta D. Berry, Host, Genealogy Roadshow (PBS)

I did not start my genealogy journey like most people. It started with a family that I am not related to: the Dwelle family. I uncovered the Dwelle family while roaming through the stacks at the Library of Michigan while in law school. My discovery— a biographical sketch of Georgia R. Dwelle— described her career as a physician, temperance worker and writer. One of the resources I used to write that sketch was The History of the American Negro and His Institutions: Georgia Edition.

That edition profiled George Henry Dwelle, Georgia Dwelle and Thomas Henry Dwelle. It was a genealogical goldmine! George was Georgia's father, born enslaved in Columbia County, Georgia on January 26, 1822. His parents were a white man, C.J. Cook, and an enslaved mother, Mary Thomas.

A well-documented life

Dr. Georgianna (Georgia) Rebecca Dwelle was born on February 27, 1883 in Albany, Georgia. Her father George was about 49 years old at the time, and her mother Mary Eliza Dickerson was about 34. Georgia was the youngest of five children and the only daughter. She attended Spelman College in Atlanta, and Meharry Medical College in Nashville. She then practiced medicine in Augusta before moving to Atlanta, where she established the Dwelle Infirmary for African American women on Boulevard Avenue.

The Dwelle Infirmary was officially incorporated in 1920, and expanded in 1935 to provide additional services to African American women in the community. Georgia was very active in the medical community; in 1924, she served as a consultant to the President’s Commission of Fifty on College Hygiene. The Commission was charged with studying hygiene practices at universities in Georgia. The Dwelle Infirmary closed in 1949, when Georgia decided to retire with her 2nd husband, Albert E. Johnson. Spelman College has named the first week of October “Georgia R. Dwelle, M.D., Making a Global Difference in Healthcare Appreciation Week.”5

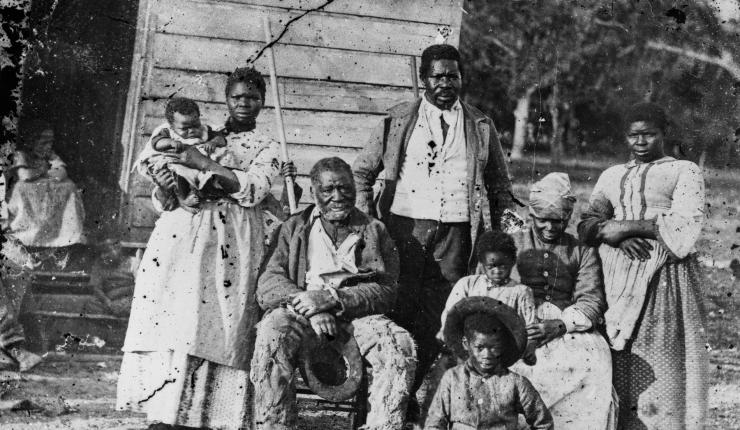

When researching your enslaved ancestors, it will likely not be as easy to find information about their parents, birth dates or birth locations. Often times, enslaved individuals did not know their birthdates. The domestic slave trade often tore families apart, making it difficult or impossible for them to reunite after Emancipation.

Finding your family’s story

Starting your family history research can be overwhelming and scary because you never know what you’re going to find. Parents, grandparents, and other family members may wonder why you want to start digging into the past. Are you looking to uncover family secrets? As they say, let the past stay in the past. Remember as you embark on this journey that you are the steward of your ancestors' stories: they are waiting to be found and retold.

How do you get started with your family history? Write a brief two to three-page autobiographical sketch—this will help you capture what you know, and what you don’t yet know about your heritage. Using the gaps you find in your autobiography as starting points, interview family members for more information. Make sure that you get family stories and recommendations on which family members to interview next. I always joke there is at least one genealogist in the family. So, let’s dig in!

The Enslaved Community

Understanding the enslaved community is essential when researching your family. This year is the 400th anniversary of the first Africans to arrive in America at Jamestown, Virginia. It’s estimated that less than 500,000 Africans who survived the Middle Passage arrived in the Colonies as enslaved individuals. The status of an enslaved individual was based on the status of their mother. If the mother was enslaved, then all of her children were enslaved. Enslaved individuals worked on large plantations, small farms, and in urban areas. A critical step in researching your enslaved ancestors is to identify the last enslaver.

How do I identify the last enslaver?

Do not assume that your ancestor had the same surname as their last enslaver. There could be a variety of reasons why your ancestor selected a particular surname. They could have taken the surname of a previous enslaver, the enslaver of a parent, or just picked a surname. It was not uncommon for African American ancestors to use multiple surnames throughout their lives. As with anything, there is always an exception to the rule. If your ancestor had an unusual or uncommon surname, they might have taken the name of their last enslaver. For unusual surnames, focus on the county where your ancestors lived in 1870. Make a list of white individuals in the county with the same surname. Then, check the list against the 1860 U.S. Federal Census Free Population and Slave Schedules. Were the individuals on your list enslavers? How many people did they enslave? What was the value of their personal property? I suggest creating a spreadsheet to keep track of this information. Repeat this process for 1850 and other census records. Below are two examples from my paternal and maternal lines.

Paternal Ancestor: Prince Ailes

When I started researching my father’s family, I discovered a distant ancestor: Prince Ailes. Prince was born enslaved in 1845 in Arkansas. In 1870, he was living in Arkansas with his mother Charlotte and his brother Frank. Since Ailes is an unusual surname, I searched for white individuals in the county with the same last name. I located two white Ailes families, Martin Ailes and Ackley Ailes. Searching the 1860 Census, I found Auckley Ailes living with her parents Walker and Martha Ailes in Union County, Arkansas. Walker enslaved six individuals in 1860; two of the enslaved were within the age range for Prince and his brother Frank. I also noticed that Ackley was born in Mississippi, the birthplace of Prince’s mother Charlotte. This gave me a starting point to explore the Ailes family and the people they enslaved. When doing enslaved genealogy, I always create a family tree for the enslavers in order to keep track of migrations.

Maternal Ancestor: Lewis Carter

In the 1870 U.S. Census, my 4th great grandfather Lewis Carter was living in Madison County, Virginia with his wife and six children. He is listed as a farm hand, with real estate valued at $4,700 and personal estate valued at $1,150.6 That was a lot of money at the time, and he had more property than anyone else on the page! How did Lewis amass substantial real and personal property holdings? Was he a free man before emancipation? Did his former enslaver give him this land? Did he purchase this land after slavery?

To answer these questions, I started with the records of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands “Freedmen’s Bureau” established by Congress on March 3, 1865. At the Library of Virginia, I found a labor contract in Madison County between Lewis Carter and Dr. John W. Taylor, dated January 5, 1866.7 For farming the land, Lewis would receive half of the crops. I wanted to know more about the crops and the land that Lewis lived on. On the 1870 U.S. Census Non-Population Agricultural Schedule, Lewis is listed as “agent” for Dr. John W. Taylor.8 Who was Dr. John W. Taylor? What was his relationship with Lewis Carter? Was he the last enslaver? So many questions, and I wanted answers!

Records used in Enslaved Ancestral Research

Once you have identified the last enslaver, or narrowed down candidates for the last enslaver, review records related to slavery and Reconstruction for each candidate. Additional Freedmen’s Bureau records to explore include education records, marriage records, registers of complaints, indentures, registers of labor contracts, and correspondence. For both large and small plantations, wills, probate records, inventories, account books, deeds, and tax records can help you discover your enslaved ancestors. Typically, larger plantations kept records regarding expenses for clothing or medical care, births and deaths, runaways, and the names of the enslaved on each plantation, if the planter had multiple plantations. For these enslavers, manuscript collections, business, and personal papers can prove to be valuable resources. These records are held at historical societies, university archives, and special collections for preservation and access, and most are not available online. Some enslavers freed or manumitted their enslaved prior to emancipation. These papers may be found in family papers, state and local libraries, and the county court house. If your ancestor was freed prior to emancipation, check the laws in the state concerning manumissions and free people of color.

Sharing your family’s story

For years, I didn’t share the story of my ancestors outside of my immediate family. I thought that no one would be interested in their story, and I didn’t really know how to share it. I have since learned that our ancestors are waiting to be discovered, to have their voices heard and their stories told. They are woven into the fabric of American history. As you go on this journey of discovery, there will be ups and downs, but your ancestors will pull you through. You are the vessel to tell their story.

Kenyatta D. Berry

Author, The Family Tree Toolkit

Host, Genealogy Roadshow (PBS)

[1] Jessie Carney Smith, ed., Notable Black American Women, Book II, (Detroit: Gale Research, Inc., 1996), 196

[2] A. B. Caldwell, ed., The History of the American Negro and His Institutions: Georgia Edition, (Atlanta: A. B. Caldwell Publishing Company, 1917), 18, 121 and 378.

[3] Ibid., 18

[4] Jessie Carney Smith, ed., Notable Black American Women, Book II, (Detroit: Gale Research, Inc., 1996), 196

[6] Year: 1870; Census Place: Locustdale, Madison, Virginia; Roll: M593_1662; Page: 38A; Image: 105058; Family History Library Film: 553161

[7] "Virginia, Freedmen's Bureau Field Office Records, 1865-1872," database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FPVG-R6F : 9 August 2017), Louis Carter, ; citing NARA microfilm publication M1913 (College Park, Maryland: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 2,414,508

[8] Census Year: 1870; Census Place: Locust Dale, Madison, Virginia; Archive Collection Number: T1132; Roll: 13; Page: 7; Line: 25; Schedule Type: Agriculture