Common Myths

by Meaghan E.H. Siekman, PhD

After many years of studying enslaved ancestors, I have identified a number of common myths about slavery in America. This article counters those myths with facts. A clear understanding of the realities of the past is essential to navigating records and appreciating the historical context of our ancestors’ lives. Knowledge about the history of slavery can also lay the framework for better insight into many of our current legal and social systems.

MYTH: “Freed people always adopted the surnames of their former enslavers.”

The issue of post-emancipation surnames is far more complex and varied than the assumption that freed individuals simply adopted the surnames of their former enslavers. In some cases, individuals did choose to adopt a former enslaver’s name, or a former enslaver’s name was assigned by the earliest record takers after emancipation. In other cases, enslaved families had used surnames consistently over generations during slavery, which were sometimes adopted from a former enslaver and sometimes chosen. For people who did not have surnames or were not allowed to use surnames during slavery, choosing a surname after emancipation was a powerful way to exercise their new freedom and forge their own paths for themselves and their descendants.1

MYTH: “Slavery in the North ended long before the Civil War.”

After the American Revolution, some northern states banned slavery in their state constitutions—although this did not happen in every state, and these laws did not prevent northern industries from profiting from slavery elsewhere. In 1777, Vermont was the first state to outlaw slavery. Massachusetts followed in 1783, after the Quock Walker case successfully established that his enslavement was inconsistent with the state constitution.2 Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, and Pennsylvania all instituted acts that provided for gradual abolition. These measures continued slavery for people who were already enslaved or who were born to enslaved people for varying terms—generally twenty years or more—depending on the state. These laws allowed for slavery in some northern states well into the nineteenth century. All residents were not officially free in New York until 1827, in Connecticut until 1848, and in New Hampshire until 1865, when the thirteenth amendment was ratified.3

MYTH: “With some exceptions, enslaved people were treated well. They were given food, shelter, and some health care.”

Slavery is slavery regardless of how “kind” enslavers might be to the people they enslaved. Under the chattel slavery system in existence in the United States, enslaved people were relegated by law to be nothing more than property. Very few laws granted any rights to the people enslaved. Enslaved people could legally be assaulted or abused by their enslavers. They could be sold away from family members and had no legal support to ensure protection and care for themselves or their children. Conditions within that system varied widely, based on the enslaver, the environment, and the labor expected of the enslaved. The Deep South is especially known for extremely harsh conditions on large plantations where the enslaved were overworked and beaten for any offense to the enslaver. Laws in all slave states supported enslavers’ rights to prevent enslaved people to gather in groups, go out at night, leave the enslaver’s property, or testify in court. Those that resisted, fought back, or tried to escape were punished at the discretion of the enslaver. Even in households where enslaved people were “treated well,” they were regulated by a legal system that gave them little to no rights.4

MYTH: “Enslaved people had no legal rights.”

While enslaved people across the United States were relegated to nothing more than property, some avenues existed for these individuals to argue for their rights in court—and many did. For example, a 1778 Virginia law banning the importation of slaves from outside the state allowed some enslaved persons who could prove that their enslavers had broken this law to argue for their freedom in court. Some lawsuits argued that enslaved people born to free mothers should also be free.5 In Massachusetts, court cases such as Brom and Bett v. Ashley and Commonwealth v. Jennison (representing the interests of Quock Walker) used the state’s new constitution to argue for freedom. Rulings for enslaved people in both these cases ultimately outlawed slavery in the state.6 So, although the legal rights of enslaved people were extremely limited, many enslaved people used laws in their favor to gain more freedoms.

MYTH: “During the Civil War, Black men fought in large numbers for the Confederacy.”

Black men were not legally allowed to serve as soldiers in any Confederate state. Virginia and other states authorized the use of enslaved labor for military purposes early in the war, but enslaved men were not given weapons for fighting. Prior to the war, laws restricted people of color from using weapons for fear of violence against Whites. This fear did not diminish with the war, so the Confederacy found other ways to use enslaved people for their cause—for instance, supporting the military as manual laborers or cooks—without arming Black men. This is not to say that no Black men took up arms against the Union, but that it was extremely uncommon. In The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies , a set of over fifty volumes that includes detailed reports from both sides of the conflict, only three reports directly mention Black men shooting at Union soldiers. Other reports mention unarmed Black laborers and one notes the capture of a group of Confederate soldiers that included a few armed Black men. No regiment of Black men fought for the Confederacy. 7

MYTH: “There were very few free Black people in the South.”

By examining laws in the South, a different story emerges about the number of free people of color who lived in the region prior to emancipation. Laws are proposed and enacted in response to perceived problems, and laws that restricted the rights of free people of color suggest the existence of a substantial free Black population.8 For example, an 1806 Virginia law stated that any freed person of color that remained in Virginia for more than a year would forfeit their right to freedom and could be sold by the Overseer of the Poor for the benefit of the parish. Free individuals could petition the state to remain longer than a year, but the state clearly did not consider the potential magnitude of the number of petitions they would receive. By 1837, the General Assembly changed the law so petitions could go to local courts.9 Prior to emancipation, most free Blacks in the United States lived in southern states—the 1860 census shows that 250,787 free people of color lived in the South, compared to 225,961 who lived in the rest of the country.10

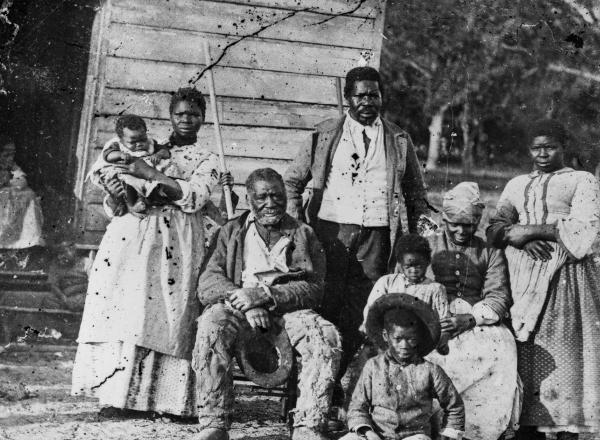

MYTH: “Enslavers commonly kept families together.”

Because enslaved people were considered to be the movable property of their enslavers, they could be bought and sold at will. Many people experienced painful separations from family members that they were powerless to control. Mothers in particular endured wrenching separations as their children were sold to different families. Following the Civil War many newly freed people placed advertisements in newspapers, as they tried to locate family who had been sold away during slavery.11

While separations were common, many families did remain together. The composition of post-emancipation households demonstrates the importance of extended family networks when separations occurred. For example, grandchildren might live with grandparents, or aunts and uncles with nieces and nephews, if parents were separated from their children. Following emancipation, a great effort was made to rebuild the connections that families had been denied during their enslavement.12

MYTH: “Slave labor was only used on plantations or rural farms.”

The labor of enslaved people was used in a variety of capacities, not just on sprawling rural farms or plantations. The 1850 and 1860 Federal Slave Schedules, lists of enslaved people created in addition to the general federal census, provide plenty of evidence on this point. Searching these records for any major city in the South will return thousands of entries of enslaved people working in households and industries in urban areas. During the eighteenth century, enslaved labor was used in northern states in almost every sector of the economy, in shipyards, building trades, artisanal shops, and commerce. Many enslavers had only one or two enslaved people in their households, and enslaver and enslaved likely worked alongside each other on smaller properties or in a specialized trade, such as in blacksmithing.13

MYTH: “The Civil War was really about states’ rights, not slavery.”

As soon as the Civil War ended, the “The Lost Cause” narrative started to spread the idea that the conflict was about states’ rights and not centered on slavery. Unusually, the popular explanation for why the Civil War occurred was not determined by the Northern victors. Instead, the South was able to construct a narrative that reflected favorably upon those who chose to secede from the Union. However, documents from the war’s beginning tell a different story. South Carolina was the first to secede, and its declaration of secession explicitly stated that the primary reason for breaking away was an “increasing hostility on the part of the non-slaveholding States to the institution of Slavery.”14 Other states also cited slavery as a primary motivation for secession. Furthermore, states relied upon the income taxes on slave labor to function, and much of the social customs of Southern planters was made possible by slave labor.15 Owning slaves was a central part of the southern social system which allowed those who owned more than twenty slaves to be considered a part of the upper class. Even considering other potential motivations, such as the economy or cultural and social differences, each of these elements were inexplicably linked to slavery.16

MYTH: “White indentured servants had it just as bad as Black enslaved people.”

While the type of labor performed by indentured servants and enslaved persons may have been similar, the terms of their bondage were different. Indentured servitude was a type of debt bondage, an agreement to work for a set amount of time to satisfy a debt. In America, indentured servants often had to repay the cost of their passage across the ocean. Sometimes indentured servitude was punishment for a crime, but such sentences still had an end point. Depending on the terms of the agreement, servants might also receive some form of payment, perhaps a plot of land, at the end of their term. Indentured servants also had laws that protected some of their rights. While their time in servitude may have been restrictive and harsh, these servants could look forward to a life after their service. Enslaved people had no such promise of future freedom and, as the legal property of the people who owned them, they had no legal recourse against injustices done to them.17

MYTH: “The majority of enslaved people worked on large plantations.”

This statement is true, but does not tell the whole story. While a majority of enslavers owned only a few people, at least half of all people enslaved lived on plantations that enslaved twenty or more people, and about a quarter were on plantations that enslaved fifty or more people. For example, in one region you may have twenty enslavers, but only two of them own one hundred or more people and the rest enslaved only two or three people, a majority of the people enslaved in that region were owned by only two people. This is what created the planter class, a status one only achieved by holding twenty or more people in bondage.18

MYTH: “Only the very wealthy could afford to enslave people.”

The vast majority of enslavers were not wealthy and owned less than five people. In these cases, enslaved people were much more likely to live in the same house as their enslavers, perhaps in the attic or a back room, but still in relative proximity. (Plantations generally had slaves quarters set apart from the main house.) The relationship between enslaver and enslaved was also different than on large estates, given the higher likelihood that the two would work alongside each other. Large wealthy estates that enslaved hundreds of people typically had overseers who managed slave labor, which meant that these enslavers might not have had personal contact with the people who worked their land.19

MYTH: “Most African Americans are descended from free people.”

The demographics of the United States just before the end of slavery present a compelling case for why most Americans of African descent have enslaved ancestors—if their forebears were here prior to emancipation. In 1860, enslaved people represented about 13% of the total U.S. population, while free Blacks comprised about 1.5%. Of the African American population, 89% were enslaved and 11% were free.20 Furthermore, even those people of color who were free by 1860 would have likely had some ancestors who were enslaved, since very few Africans came to the Americas as free people.

MYTH: “Millions of Africans were brought to the United States to be enslaved.”

Looking at the statistics for the entire duration of legal slavery in the Americas between 1525 and 1866, 12.5 million Africans were transported out of Africa, with 10.7 million surviving the overseas voyages to land in North America, South America, and the Caribbean. Of those 10.7 million, however, only about 388,000 people were shipped directly to North America, a small percentage of the total slave trade to the Americas.21 An act of Congress in 1800 made it illegal to engage in the slave trade between nations and, by 1808, the Act Prohibiting the Importation of Slaves took effect, so the legal trafficking of slaves from Africa then ceased.

Notes

1 For some examples see Meaghan E.H. Siekman, “Slave Surnames,” Vita Brevis blog, May 26, 2021, vitabrevis.americanancestors.org/2021/05/slave-surnames.

2 “Instructions to the Jury in the Quock Walker Case, Commonwealth of Massachusetts v. Nathaniel Jennison (1783)” National Constitution Center website, constitutioncenter.org/the-constitution/historic-document-library; search for “Quock Walker.” [Okay to add this endnote?]

3 For more information about gradual emancipation acts in northern states, see Joanne Pope Melish, Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and “Race” in New England, 1780–1890, (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2000); Jared Ross Hardesty, Black Lives, Native Lands, White Worlds: A History of Slavery in New England (Amherst, Mass.: Bright Leaf, 2019); and Christy Clark-Pujara, Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island (New York: NYU Press, 2018).

4 See Ira Berlin, Generations of Captivity: A History of African-American Slaves (Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press), 2003.

5 See the “Freedom Suits” collection at Library of Virginia, Virginia Untold: The African American Narrative, lva-virginia.libguides.com/virginia-untold.

6 Original court records are in the custody of the Supreme Judicial Court, Division of Archives and Records Preservation. Information about the Quock Walker cases is available at The Long Road to Justice,.longroadtojustice.org/topics/slavery/quock-walker.php.

7 United States War Department, et al., The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office 1880–1901), loc.gov/item/03003452.

8 See Ira Berlin, Slaves without Masters: The Free Negro in the Antebellum South, (New York: Pantheon Books), 1974.

9 June Purcell Guild, Black Laws of Virginia: A Summary of the Legislature Acts of Virginia Concerning Negroes From Earliest Times to the Present (Richmond, Va.: Whittet & Shepperson, 1936), catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000340605.

10 Erin Bradford, “Free African American Population in the U.S.: 1790–1860,” from the University of Virginia Library, ncpedia.org/sites/default/files/census_stats_1790-1860.

11 See Heather Andrea Williams, Help Me to Find My People: The African American Search for Family Lost in Slavery, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press), 2012.

12 Ira Berlin, The Making of African America: The Four Great Migrations (New York: Viking, 2010), 80–87.

13 Kris Manjapra, Black Ghost of Empire: The Long Death of Slavery and the Failure of Emancipation (New York: Scribner, 2022), 11–15.

14 Declaration of the Immediate Causes which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union (Charleston, S.C.: Evans & Cogswell, 1860), atlantahistorycenter.com/app/uploads/2020/11/SCarolina-Secession-p1-13.pdf.

15 George Ruble Woolfolk, “Taxes and Slavery in the Ante Bellum South,” Journal of Southern History 26 (May 1960), pp. 180–200.

16 Kenneth M. Stampp, The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South (New York: Vintage Books), 1956.

17 For more information on indentured servitude and slavery, see Kenneth Morgan, Slavery and Servitude in Colonial North America (New York: New York University Press), 2001.

18 See Stampp, The Peculiar Institution [note 15].

19 See Leslie Howard Owens, This Species of Property: Slave Life and Culture in the Old South, (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press), 1976.

20 “Data Analysis: African Americans on the Eve of the Civil War,” in Patrick Rael, Black Activism in the Antebellum North: A Lesson Plan (Brunswick, Me.: Bowdoin College, 2005). bowdoin.edu/~prael/lesson/tables.htm.

21 Henry Louis Gates, Jr., “How Many Slaves Landed in the U.S.?,” The Root, January 6, 2014, theroot.com/how-many-slaves-landed-in-the-us-1790873989; “Summary Statistics,” Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, at Slavevoyages .org.