African American Genealogy

Introduction

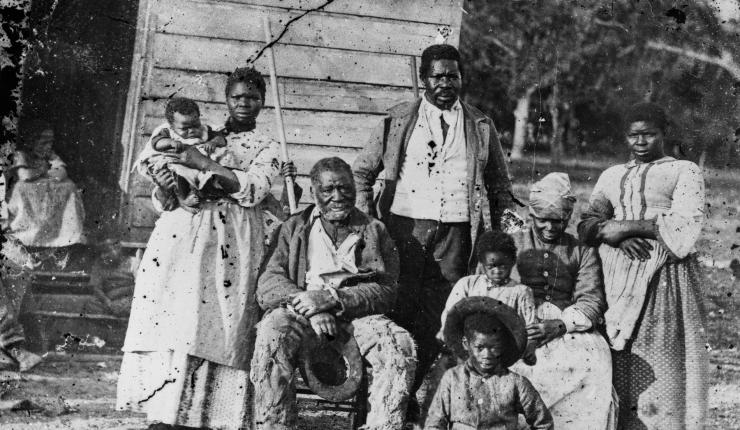

Researching African American ancestors can be challenging and often requires creative researching methods. Many African Americans find it difficult to trace their family earlier than the 1870 United States Federal Census, the first federal census following emancipation and the first to record many formerly enslaved individuals by name. Locating records of enslaved ancestors prior to emancipation requires researching the enslaver’s family since most of the records where the enslaved may be named, such as probate, account, and deed records, will all be in the enslaver’s name. Locating ancestors that were free prior to emancipation also has unique challenges as records are dispersed and can be difficult to navigate. The process of locating African American ancestors can be time consuming but the effort can be extremely rewarding.

Jump to: Historical Context | Getting Started | Research Guides | Records for African American Genealogy Research | Other Resources | Societies, Library, Museums, and Websites

Historical Context

Most individuals of African descent in the United States have ancestors whose lives were shaped by slavery and racial injustice. It can be emotional and sometimes disturbing work facing the realities of the past. Enslaved people were denied many rights and are usually only recorded within records of the people that enslaved them. Black ancestors that were free during slavery faced challenges that limited their access to jobs, education, and land. Understanding the legal and social status of Black ancestors is an important part of discovering records or finding sources that give a better sense of what they may have experienced in their lives. In addition to many of the standard genealogical sources, you will also want to research laws that may have influenced your ancestors lives since they could provide clues on further record sets to examine.

Slavery had a devastating effect on many families. It was not uncommon for family members to be separated and sold to different enslavers. Separation from a birth family also produced environments where unrelated people supported each other like family, creating bonds that lasted after emancipation. This can create challenges for the genealogist piecing together families and requires the examination of all known friends, neighbors, and associates of an ancestor to get as much information about them as possible.

Surnames can also prove challenging. Many newly emancipated people were given the surnames of their former enslavers, either by choice or because they were assigned to them by record keepers. Sometimes individuals rejected these surnames and may appear with a different surname in records later in their lives. It was also not uncommon for enslaved people to have surnames that were passed down through generations in their own families during slavery. Sometimes these names came from a former enslaver or were just adopted by choice and passed down. Due to this, you can have blood relatives with different surnames and also unrelated people who were owned by the same enslaver with the same surname.

Getting Started

The 1870 United States Federal Census is the first census that recorded formerly enslaved individuals by name. If you are working backward through census records, you may hit this census and not know how to go further back in time. The 1860 and 1850 Federal Census had a separate slave schedule that recorded the enslaver’s name and a description by age, sex, and color of the individuals they enslaved.

Identifying an enslaver is key to locating records for an enslaved person prior to emancipation. Pay attention to the location of your ancestor in 1870, since it is likely they did not move far after emancipation, as well as the last names that they and their neighbors or associates used since one of them may have adopted it from a former enslaver.

Research local slave laws or laws concerning free people of color. Understanding laws can lead you to further record sets. Research local slave laws or laws concerning free people of color. For example, if you discover that all free people of color needed to pay a fee or register with the local authorities, you know to look for those registers. Many universities or scholarly organizations have put together timelines of slavery laws, and a simple internet search such as “Virginia Slave Laws” can help you locate information.

Resources for Slave Laws

Slavery in the North includes articles about the evolution of slavery laws and laws pertaining to free people of color in northern states–namely Connecticut, Delaware, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It also includes information about laws relating to people of color in Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin. Each article includes a source list to help you locate even more information.

Maryland

- Guide to the History of Slavery in Maryland

- Slavery and Freedom in Maryland (scroll down for a timeline)

- Black Slaves in Maryland includes a discussion of laws pertaining to free people of color.

Virginia

North Carolina

- An Act Concerning Slaves and Free Persons of Color

- Documents at UNC relating to the legal status of African Americans

South Carolina

- South Carolina Slave Codes

- The Legal Status of the Slave in South Carolina, 1670-1740

- Excerpts from South Carolina Slave Cod of 1740 No. 670

Georgia

- Slave Laws of Georgia, 1755-1860

- A Brief Timeline of Georgia Laws Relating to Slaves, Nominal Slaves, and Free Persons of Color

- Slave Codes of Georgia (published 1848)

Florida

- Toward a More Humane Oppression: Florida’s Slave Codes, 1821-1861 (article begins on page 52).

- Excerpts from Florida State Constitution [Florida’s “Black Codes”] (1865 )

- Florida Black Codes

Alabama

Mississippi

- Mississippi Encyclopedia Slave Codes

- Mississippi Black Code, 1865

- A Contested Presence: Free Black People in Antebellum Mississippi, 1820-1860

Louisiana

Arkansas

- Encyclopedia of Arkansas Slave Codes

- Slavery and the Arkansas Supreme Court

- Arkansas Black Codes (February 1867)

Texas

- Texas Slavery Project: The Laws of Texas

- Handbook of Texas: Slavery also see Black Codes

- Texas Slave Codes

Tennessee

Kentucky

- Slavery Laws in Old Kentucky

- Kentucky Slavery Codes (1794-1850)

- Kentucky Law Concerning Emancipation or Freedom of Slaves

Missouri

Research Guides

Resources at the American Ancestors Research Center

The guides listed below are available not only at the American Ancestors Research Center but also at many local libraries (see WorldCat) and through online booksellers. Click the links below to view publication information.

Genealogist's Guide to Discovering Your African American Ancestors: How to Find and Record Your Unique Heritage by Franklin Carter Smith, 2003.

Finding a Place Called Home: A Guide to African American Genealogy and Historical Identity by Dee Woodtor, 1999,

African American Genealogy: A Bibliography and Guide to Sources by Curt Bryan Witcher, 2000.

Black Roots: A Beginners Guide to Tracing the African American Family Tree by Tony Burroughs, 2001.

African American Resources at the New England Historic Genealogical Society: A Selected Bibliography by New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2010.

Resources at FamilySearch.org

The Family History Library in Salt Lake City has extensive materials about researching your African American ancestor. First, check out their collection of Research Wiki articles. Type your search terms into the box on the page. Next, explore the Digital Books collection. Finally look for specific records using their databases.

African American Genealogy, Research Wiki Article

African American Digital Bookshelf, Digital Books

Quick Guide to African American Records, Research Wiki Article

Other Resources

Kluskens, Claire, "Federal Records that Help Identify Former Slaves and Slave Owners" National Archives

"African American Genealogical Research" Library of Congress

Records for African American Genealogy Research

Census Records

It can be difficult to trace African American ancestors prior to the 1870 United States Federal Census. If an African American ancestor was free prior to the end of slavery you may be able to locate them on earlier census records under their own name. The 1850 and 1860 United States Federal Censuses recorded all the free individuals in a household by name. In earlier census records, only the head of the household’s name will appear, but the record contains the number of people in each age range in the household. Free African Americans were recorded under the columns for “Free Colored Persons.” Census records are available through Ancestry.com and FamilySearch.org.

If your ancestor was enslaved, you will need to know the likely enslaver. In 1850 and 1860 the United States recorded slave schedules along with the federal census. These records can be accessed through Ancestry.com, FamilySearch.org, and the National Archive. A majority of these records only provide the enslaver’s name, giving a description of the age, sex, and complexion of the enslaved in the household. If the enslaver’s name is not known, search for your ancestor’s surname in the area where they were living in 1870. For a variety of reasons, formerly enslaved people often had the surnames of their former enslavers. This is not always the case, but it can be a good starting point in trying to work backward in time.

Many published collections have compiled information of African Americans in census records for various states and regions. The sources include:

Free Negro heads of families in the United States in 1830, together with a brief treatment of the free Negro by Carter G. Woodson, American Ancestors Database. An online version is available at FamilySearch.org.

Slaves and Nonwhite Free Persons in the 1790 Federal Census of New York by Gilbert S. Bahn, 2000.

Free Black Heads of Household in the New York State Federal Census, 1790-1830 by Alice Eichholz and James M. Rose.

Census Occupations of Afro-American Families on Staten Island, 1840-1875 by Richard B. Dickenson, 1981.

State Censuses

Some states have special state census collections which may capture your ancestor either as a Free Person of Color or as a newly emancipated person, before 1870. Some of the records are only viewable at a Family History Center or affiliate library.

"Alabama, U.S., State Census, 1820-1866"

Georgia: "State census records, 1838-1879"

"Mississippi, U.S., State and Territorial Census Collection, 1792-1866"

“Missouri State and Territorial Census Records, 1732-1933”

“South Carolina, State and Territorial Censuses, 1829-1920 (includes the 1869 census)”

Church and Cemetery Records

Church records can contain a wealth of information including valuable vital records of births, marriages, and deaths. Northern Anglican, Catholic, and Quaker church records can also contain information about manumissions and admissions of free African Americans to congregations. Church records are housed in a variety of places and sometimes can only be located at the church if it is still in operation. Identifying an ancestor’s congregation can lead to more records on the individual and their family. There are several repositories that have programs focused on collecting African American church records.

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, a part of the New York Public Library, actively collects church records as a part of its Preservation of the Black Religious Heritage Project.

Amistad Research Center housed in Tulane University’s Tilton Memorial Hall in New Orleans, Louisiana, also collects church records in addition to the American Missionary Association Collection.

The Library of Virginia produced "African American Church Histories in the Library of Virginia", which contains a full list of the resources they hold in their library as well as a list of organizations, biographies of church leaders, and manuscript resources.

"The Church in the Southern Black Community" contains a collection of autobiographies, histories, church documents, and other materials to document the history of the church in African American communities.

Many historically Black cemeteries have organizations or projects that have been formed around cataloging and maintaining them that could help give you more information on the people buried there, such as God’s Little Acre, at the Common Burial Grounds, Newport, Rhode Island.

Court: Manumission Documents

The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution made slavery and indentured servitude illegal in all areas subject to United States jurisdiction. Prior to the passage of this amendment, individual manumission documents and state-wide abolition acts in the northern states can provide information about ancestors that were freed prior to the federal abolition of slavery. For example, Pennsylvania passed “An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery” on 1 March 1780 which specified that those born into slavery after the passing of the act would be free upon reaching the age of 21. The Act required that slaves be registered and those not recorded were to be freed. Due to this stipulation in the law, there are records of enslavers registering their enslaved. FamilySearch.org has some of these records at the county level. Check their catalog for your ancestor’s county. They also have a summary collection titled "Indenture and Manumission Records, 1780-1939."

The New Orleans Public Library has a unique "Index to Slave Emancipation Petitions, 1814-1843."

The District of Columbia was the only place in the United States in which the Federal government provided monetary compensation to ex-slaveholders in 1862 when it passed a law to abolish slavery in the nation’s capital. Records of the petitions for compensation as part of this law have been compiled into a published volume, Compensated Emancipation in the District of Columbia: Petitions under the Act of April 16,1862 . The claims include information on the claimant, the names of those in their service freed under the law, and the amount of compensation awarded. Often, they include additional information about the formerly enslaved, including where they were born and their occupation.

Compensated Emancipation in the District of Columbia: Petitions under the Act of April 16, 1862 by Dorothy S. Provine, 2005.

There are some published sources on the manumission and emancipation of slaves in other states, including:

Chains Unbound: Slave Emancipations in the Town of Greenwich, Connecticut by Jeffrey B. Mead,1995.

Freedom Papers: 1776-1781 by M. M. Pernot, editor, introduction by Clement Alexander Price,1984.

The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record published a number of articles on the births and manumission of slaves in New York. Volumes 1–54 are available online through American Ancestors. Some notable articles include:

- Alice Eichholz and James M. Rose, “Slave Births in Castleton, Richmond County, New York,” The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, Vol. 110, No. 4 (Oct. 1979), pp. 196–197.

- Alice Eichholz and James M. Rose, “Slave Births in New York County,” The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, Vol. 111, No. 1 (Jan. 1980), pp. 13–17.

- Henry B. Hoff, “Researching African-American Families in New Netherland and Colonial New York and New Jersey,” The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, Vol. 136, No. 2 (Apr. 2005), pp. 83–95.

- Terri Bradshaw O'Neill, “Manumissions and Certificates of Freedom in the New York Secretary of State Deeds,” The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, Vol. 139, No. 1 (Jan. 2008), pp. 72–73.

Directories

Ancestry.com has numerous city directories from across the country in the "U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995" collection. While not as comprehensive as Ancestry.com, Fold3.com’s city directories collection, may include additional years for selected cities. For example, Ancestry’s Washington, D.C. collection begins with 1862, while Fold3’s collection goes back to 1822.

When searching for ancestors of African descent, keep in mind that some directories had an entirely different section for people of color. When they are included in the general list of residents, it is not uncommon for directories to designate people of color with an asterisk, the letter “C,” or the abbreviation “Col.” You may also notice during your research that race was subjective to the person recording the information, so your ancestor may appear in the “colored” section one year but not the next.

Freedmen’s Bureau

The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, often referred to as the Freedmen’s Bureau, was established by the War Department by an act of 3 March 1865. It oversaw providing relief and education to refugees and the newly emancipated. The records of the Freedmen’s Bureau often contain the names, ages, and occupations of freedmen and can include the names and residences of their former enslavers. The records vary by state but typically include a range of records including work contracts, bank records, marriage registers, school and hospital records, census data, and military service.

The Freedmen’s Bureau Project is a fantastic project which recently indexed thousands of digitized Freedmen’s Bureau records in a searchable database. This is the first comprehensive search engine for examining the Freedmen’s Bureau records. The database is housed at FamilySearch, and if you are having difficulty searching by name alone as the main site suggests you do, you can go into individual collections within the Freedmen’s Bureau records through the FamilySearch catalog. Ancestry.com also now has Freedmen’s Bureau records available for search in the "U.S. Freedmen’s Bureau Records,1865-1878" collection. Since databases may be indexed differently, searching multiple databases for the same records may yield different results.

You can also access Freedmen’s Bureau records at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. For a description of the records collected by the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands by state, see:

Preliminary Inventory of the Records of the Field Offices of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands compiled by Elaine Everly and Wilna Pacheli, American Ancestors 5th Floor Stacks E185.2 .U5877 1973. An online version is available at FamilySearch.org.

The Freedmen’s Bureau Online: Records of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands also contains databases and a search option for records that have been transcribed to the site. This is a good starting point to quickly see if an ancestor is included in any of its databases, though it does not include all of the Freedmen’s Bureau’s records and additional searching for records may be necessary.

Labor contracts collected by the Freedmen’s Bureau may contain information about the former enslaver. Freedmen and women frequently continued to work the land where they were previously enslaved, but they had work contracts with the owner of the land, often their former enslaver. Since many lands in the South were abandoned or confiscated during this time, be sure to research the landowner in these contracts to ensure that they were living there during slavery before making an assumption that they are the previous enslavers. There are many instances of people from other parts of the county coming to the South to make sure those lands were productive and therefore they may not be the former enslavers.

Bank records often contain a great deal of genealogical information since the applications for an account asked about birthplace, residency, family members, and sometime former enslavers.

To focus on the Freedman’s Bank Records, try:

- "Freedman’s Bank Records", available at FamilySearch.org.

- The Freedman's Savings and Trust Company and African American Genealogical Research by Reginald Washington, American Ancestors, 5th Floor Stacks CD3020 .P72 v.29 no.2 Summer 1997. An online version of the article is available at the National Archives.

- North Carolina Freedman's Savings & Trust Company Records abstracted by Bill Reaves; Beverly Tetterton, editor, American Ancestors, 5th Floor Stacks E185.96 N67 1992.

American Ancestors holds some collections relating to the Freedmen’s Bureau.

Records of the Superintendent of Education for the State of Texas, Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, 1865-1870, American Ancestors, Microtext Floor CD3027.M5 N3 M822, and online at FamilySearch.org.

Land, Probate, and Property

If your ancestors owned land, you may be able trace the ownership of the land back in time to determine when the family acquired it and how. If your ancestors were free and owned property during slavery, the deeds may reveal more details about their occupation, people they were associated with, or how they gained their freedom.

Enslaved individuals were property therefore deeds, account records, or other property records may include enslaved people by name. Once you have determined a likely enslaver, the next step is to locate any probate, land, or account records for that individual since these are the most likely documents that will name an enslaved ancestor. The whereabouts of these records will vary by geographic location, but many of these types of records are available to search or browse through FamilySearch.org, Ancestry.com, or AmericanAncestors.org. Some examples in the American Ancestors collection are:

Nathan Holbrook Glover papers, 1647-1982 (bulk 1686-1744, 1793-1927), American Ancestors, Manuscripts Mss 319. This is a collection of mostly business papers of the Glover Family from 1647–1982 in Massachusetts. The collection includes slave deeds from 1704 and 1744.

Dorothea Barton Cogswell Papers, 1647-1975 (bulk: 1710-1853 ), American Ancestors, Manuscripts Mss 405. This collection contains original account and personal papers, probate records, and slave bills for the Cogswell and Russel Families of Gloucester, Ipswich, and Rowley, Massachusetts.

Military Records

African Americans have participated in every military conflict in the United States. For service in the Civil War, refer back to the Freedmen’s Bureau records since they managed the payments to the U.S. Colored Troops. Fold3.com also has a page dedicated to the records for African American soldiers. For any war, the best way to start is to research the history of the service of Black soldiers to provide some context and get an idea of what records may exist.

Resources at American Ancestors Research Center

Black Soldiers - Black Sailors - Black Ink: Research Guide on African-Americans in U.S. Military History, 1526-1900 by Thomas Truxtun Moebs,1994.

Minority military service, New Hampshire, Vermont, 1775-1783 published by National Society Daughters of the American Revolution,1988-91

"Strong and brave fellows": New Hampshire's black soldiers and sailors of the American Revolution, 1775-1784 by Glenn A. Knoblock, 2003.

On the Trail of the Buffalo Soldier: Biographies of African Americans in the U.S. Army, 1866-1917 compiled and edited by Frank N. Schubert, 1995.

Black Valor: Buffalo Soldiers and the Medal of Honor, 1870-1898 by Frank N. Schubert,1995.

Black Union Soldiers in the Civil War by Hondon B. Hargrove, 1988.

Don’t forget to check WorldCat.org for titles at your local library.

Newspapers

GenealogyBank.com has a large collection of Black newspapers from across American starting in 1827 through the 20th century. Even if you cannot find mention of your direct ancestor in these papers, they do provide a great deal of context to life as an African American across time. Additionally, sites such as GenealogyBank.com and Newspapers.com provide digital access to thousands of mainstream newspapers to search for information about your ancestors.

Freedom on the Move is a project out of Cornell University that is working to create a searchable database of run-away slave advertisements in newspapers. These records often include a detailed description of the fugitive’s physical appearance as well as any trades or skills they possessed. The inclusion of these details were to help ensure capture or prevent the individual from gaining employment.

Tax Records

Many tax records included areas to note the taxes collected for enslaved people owned by the person being taxed. In many states, in the South in particular, the tax on the enslaved was a vital part of the economic structure, so the number and value of enslaved people were well documented in tax records. Unfortunately, these records never include names of the people enslaved. However, if your ancestors were free people of color, they would likely be noted as such when their taxes were collected. The whereabouts of these records will vary by geographic location but be sure to check records on the town and county level where your ancestors lived.

Vital Records

Vital records are the backbone of genealogical records. If your ancestor was a free person of color prior to the Emancipation Proclamation, their vital events may have been recorded in the local records where they lived. Often the information can be found in church records where they are either recorded in a separate section for people of color, or the records make some notation to indicate the individual is a person of color. In regions where local laws made no provision for marriages between enslaved people of color, the Freedmen’s Bureau was authorized to recognize and record the marriages of the newly emancipated. The records include the states of Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia. The District of Columbia is also included.

FamilySearch.org: "United States, Freedmen's Bureau Marriages, 1861-1872"

Voter Registration

Voter registration records are a good resource for locating male ancestors shortly after the end of the institution of slavery. On 23 March 1867, U.S. Congress passed an act that extended the Reconstruction Act to include the registration of qualified voters. The Act required that all qualified male citizens over the age of twenty-one be registered to vote. The Act also required those registering to vote to take an oath of allegiance to the United States. Unfortunately, voter registration lists do not survive in every state, but if they are available, they can provide valuable information about ancestors including their name and place of residency. In most states, these are the earliest statewide records of African Americans following slavery.

Most of these records are only available at the state archives for their respective states. Some records are available digitally through FamilySearch.org. A keyword search of their catalog for “1867 Voter Registration” will produce the collections available for viewing either at home, the American Ancestors Research Center, or a Family History Center.

The list of some online state specific collections below pulls from FamilySearch.org, Ancestry.com, and state Archive Departments.

- Alabama:

- “Alabama Voter Registration and Poll Tax Cards, 1834-1981”

- Alabama Department of Archives and History 1867 Voter Registration Records

- Georgia:

- Louisiana: "Louisiana, Orleans and St. Tammany Parish, Voter Registration Records, 1867-1905"

- Mississippi: "Mississippi, Voter Registration, 1871-1967"

- Texas: "Texas, U.S., Voter Registration Lists, 1867-1869"

Other Resources

Maps and the Transatlantic Slave Trade

In Motion: The African-American Migration Experience is a great place to get started if you are trying to trace and understand your ancestor’s migration. The site includes information on the Transatlantic Slave Trade, typical paths taken by those who escaped slavery, and migration patterns out of the South following emancipation. The site also includes resource on voluntary immigration from African and Haiti. The site includes helpful maps that depict the typical paths taken in each migration.

SlaveVoyages, created by a consortium of universities and hosted by Rice University, describes not only the transatlantic migration, but also the intra-American trade. It is replete with maps, databases, manuscripts, and images for understanding the paths taken by ancestors.

Caribbean Ancestry

There are many records available to research ancestors from the Caribbean and a number of these resources are available online. The Family History Library has a number of collections for Barbados and the Caribbean Islands that are searchable, including Caribbean Births and Baptisms.

There are several resources to help identify Caribbean enslavers. The University College of London has also created a database of British enslavers that filed claims for compensation in 1833 when parliament abolished slavery. This is a searchable database called "Legacies of British Slave-Ownership" that includes information about the claimant and the extent of the claim. Most of these enslavers filed claims for slaves in the Caribbean. Dr. Oliver Gliech has compiled a list of Plantation Owners of St. Domingue which is helpful in identifying enslavers that were a part of the French Colony of St. Domingue.

Resources at the American Ancestors Research Center

There are a few source books at the American Ancestors Research Center that are particularly useful for Caribbean research. And don’t forget WorldCat.org to check if your local library has a title.

A Tree without Roots: The Guide to Tracing British, African and Asian Caribbean Ancestry by Paul Crooks, 2008.

My Ancestor Settled in the British West Indies: Bermuda, British Guiana and British Honduras by John Titford, 2011.

Tracing Ancestors in Barbados: A Practical Guide by Geraldine Lane, 2006.

A Brief History of the Caribbean: From the Arawak and the Carib to the Present by Jan Rogoziński, 1992.

Caribbean Historical and Genealogical Journal,1993.

Free People of Color

If you are looking for free people of color in the Northeast during or following slavery, you will benefit from seeing what types of collections your local historical society holds. Many repositories have been actively working to develop guides for locating material in their collection that relates to African American History. For example, the Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society Related to African American History includes sections on freedmen, abolition, and emancipation as well as more recent African American organizations and civil rights that may prove helpful if you are searching in Massachusetts.

Other town, county, and state level historical societies may have similar lists for their region. For example, see the Georgia Archives for their African American resources, including the Free Persons of Color Registers, 1780-1865.

A great resource to search for free African Americans in the South and mid-Atlantic is Paul Heinegg’s website, Free African Americans of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland, and Delaware. The site compiled information from tax lists, registry lists, wills, deeds, and other records on free African Americans prior to passage of the Thirteenth Amendment. More recent articles on the site also include information from Tennessee, Indiana, and Illinois.

Hard copies of some of the compilations are available at the American Ancestors Research Center:

- Free African Americans of Maryland and Delaware: From the Colonial Period to 1810 by Paul Heinegg, 2000.

- Free African Americans of North Carolina, Virginia, and South Carolina from the Colonial Period to about 1820 by Paul Heinegg, 2005.

Other sources at the American Ancestors Research Center include:

Free African Americans of Maryland 1832: Including: Allegany, Anne Arundel, Calvert, Caroline, Cecil, Charles, Dorchester, Frederick, Kent, Montgomery, Queen Ann's, and St. Mary's Counties by Jerry M. Hynson, 1998.

Somebody knows my Name: Marriages of Freed People in North Carolina County by County compiled by Barnetta McGhee White, 1995.

Indigenous Connections

Many African American families have family lore indicating a connection to an Indigenous community. Understanding the history of African American and Native relations will help determine a potential connection. It is possible that African ancestors ran away to Indigenous groups or that two marginalized groups in a region intermarried. While these explanations are often the most poetic, they are not the only possible connections.

One of the possible scenarios is that an African American ancestor was a former slave of an American Indian enslaver. This is the most likely scenario for which documentation exists. Prior to the end of slavery, several Native Nations enslaved Africans, namely the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole, or the so-called “Five Civilized Tribes.” When slavery was abolished, some of these formerly enslaved people became citizens of the Native Nations to which they were previously enslaved. The enrollment cards created by the Dawes Commission to determine who could gain citizenship can be a valuable resource to learning more about ancestors that were freedmen of these Native Nations.

Black Indian Genealogy Research by Angela Y. Walton-Raji, 1993. A good reference book for understanding how to search for an American Indian connection.

The enrollment records of the Dawes Commission are available on microfilm through the United States National Archives, but there are indexes to the records that can be searched first to determine the likelihood that an ancestor is included on the rolls.

Index to the Cherokee Freedmen Enrollment Cards of the Dawes Commission, 1901-1906 by Jo Ann Curls Page,1996. FamilySearch.org has this same source available digitally.

You can search the index to the final Dawes Commission rolls online through Access Genealogy. These are the final rolls of those accepted as citizens, so it is not an exhaustive index of the applicants. It is helpful to also examine records for rejected applications since they contain valuable genealogical information.

Genealogies and Biographies at the American Ancestors Research Center

Slaves in the Family by Edward Ball, 2001.

Homelands and Waterways: The American Journey of the Bond family, 1846-1926 by Adele Logan Alexander,1999.

Workbook on the Families of Color of Nashoba Valley compiled by George W. Dewey, Joy Hartwell Peach, Joann Heselton Nichols, 2004.

The Hemings Family of Monticello by James A. Bear,1980.

Descendants of Shandy Wesley Jones and Evalina Love Jones: The Story of an African American Family of Tuscaloosa, Alabama by Ophelia Taylor Pinkard and Barbara Clayton Clark,1993.

The Ancestors and Descendants of Theodore Roosevelt Whitney (1902-1979): Profile of an African-American Family by Harold Coleman Whitney,1994.

Passing for White: Race, Religion, and the Healy Family, 1820-1920 by James M. O'Toole, 2002.

African American Biographical Database The largest electronic collection of biographical information on African Americans, 1790–1950.

The Life of William J. Brown of Providence, R.I.: With Personal Recollections of Incidents in Rhode Island foreword by Rosalind C. Wiggins; introduction by Joanne Pope Melish, 2006.

Captain Paul Cuffe's logs and letters, 1808-1817: A Black Quaker's "Voice from within the Veil" edited by Rosalind Cobb Wiggins; with an introduction by Rhett S. Jones,1996.

A Gentleman of Color: The Life of James Forten by Julie Winch, 2002.

Prince Estabrook: Slave and Soldier by Alice M. Hinkle, 2001.

Check WorldCat.org for titles at your local library.

Periodicals

African American Family History Association Inc., Newsletter

Journal of the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society

Manuscript Collections at the American Ancestors Research Center

Gaines Funeral Home Records, 1929-1934, (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania)

The Gaines Funeral Home was established by George W. Gains in 1919 in the historically African-American Homewood neighborhood of Pittsburgh. It is the longest-operating, African-American-owned business in Western Pennsylvania. The records include names of deceased, vital information, names of parents and next of kin, and places of the funeral service and internment.

Diary of Josiah Freeman Bumstead, 1834 January-June by Josiah Freeman Bumstead, online at American Ancestors Digital Library & Archives.

Josiah Freeman Bumstead was the superintendent at the Belknap Street Sunday School, African Baptist Church. This manuscript collection contains his diary between January and June 1834. The Massachusetts Historical Society holds Josiah Freeman Bumstead’s letters from 1841–1846.

1st Kansan Colored Vol. Reg't., 1863-1865 by Ethan Earie, online in American Ancestors Digital Library & Archives.

This collection contains the original account book of Capt. Ethan Earle, commander of First Kansas Colored Volunteer Regiment Company F. The documents include a roll of the soldiers in Company F and a list of it field, staff, and line officers. The collection also includes a written history of the regiment.

Saddle River Reformed Dutch Church by Herbert S. Ackerman and Arthur J. Goff.

This collection consists of transcriptions of admissions (1812–1924), dismissals (1866–1924), marriages (1813–1922), and baptisms (1811–1890) of the Saddle River Reformed Dutch Church in Bergen County, New Jersey. It includes African American baptisms, marriage, admissions, and burials.

Webinar

African American Resources at American Ancestors

Live broadcast: March 26, 2015

Presented by: Meaghan E. H. Siekman

Description: There are hundreds of resources available at American Ancestors to assist you with researching African American ancestors: from published genealogies to local histories, original manuscripts, and rare documents to online databases. Gain valuable how-to tips and techniques from researcher Meaghan E. H. Siekman.

Societies, Library, Museums, and Websites

Many organizations offer websites dedicated to assisting family historians in their search for their African American ancestors. The list below includes national as well as state specific organizations.

National Organizations

African-American Historical and Genealogical Society

State Organizations

- Alabama: Black Belt African American Genealogical and Historical Society

- California:

- Colorado: Black Genealogy Search Group

- Illinois: African-American Cultural & Genealogical Society of Illinois, Inc. Museum

- Indiana: Indiana African American Genealogy Group

- Kentucky: African American Genealogy Group of Kentucky

- Louisiana: Louisiana Creole Research Association

- Michigan: Fred Hart Williams Genealogical Society

- Missouri:

- New York: Afro American Historical Association of the Niagara Frontier

- North Carolina: The North Carolina African-American Heritage Commission

- Ohio: Oberlin African-American Genealogy and History Group

- Pennsylvania: African American Genealogy Group

- South Carolina: Old Edgefield District Genealogical Society

- Virginia: Middle Peninsula African-American Genealogical & Historical Society of Virginia

Websites

A collaboration among the GU272 descendants, the Georgetown Memory Project, and American Ancestors. Includes a searchable online database of genealogical data for GU272 families, oral histories of more than 40 descendants, and educational material about genealogy.

Georgetown Slavery Archive with images of original documents

This project, initiated in 2011 by the Virginia Historical Society, culls information about enslaved Virginians from manuscript and other collections. The project migration to the Library of Virginia in 2019 and is now part of the Virginia Memory collection.

This center seeks to develop state specific Resource Guides to aid patrons researching their African American genealogy.

Enslaved: Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade

This website, a collaboration of Michigan State University, University of Maryland, and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, offers users the chance to search for people across multiple project and databases. The focus is on the enslaved, the enslaver, the trade, and those who worked to emancipate slaves.

Runaways and fugitives and their stories as found in newspaper ads create the focus for this website.

Digital Library on American Slavery

The Digital Library on American Slavery includes documents from the Race and Slavery Petitions Project, the North Carolina Runaway Slave Advertisements Project

Slave Sales in Louisiana, Afro-Louisiana History and Genealogy, 1718-1820

This unique database was recovered from the courthouse at Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana. The records include inventories describing over 100,000 enslaved individuals being delivered to Louisiana. Search by name, gender, or racial designation (i.e., black, mulatto, octoroon).

North American Slave Narratives

This collection collects books and articles about the struggle for human rights. The goal was to make the narratives of enslaved people accessible at a single location.

The African-American Gateway is housed at the Allen County Public Library and offers several unique databases for researching African American ancestry.

American Memory – Slaves and the Courts 1740-1860

As part of the Library of Congress’s American Memory Collection, the collection includes trials, cases, reports, arguments, accounts, and other items of importance.