Reflections on 10 Million Names

Article first published in American Ancestors Magazine edition Summer 2023, vol. 24, no. 2.

Author: Kendra Taira Field, PhD , the Chief Historian of the 10 Million Names Project, is Associate Professor of History and Director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at Tufts University.

When I first moved to Boston, a city defined by its memorialization of the American past, I taught an undergraduate seminar on slavery in North America.

I discovered that many of my students had personal ties to the material, and several had access to intriguing family stories and bits and pieces of oral

history. The year was 2014, nearly a decade ago now, and because I owed my career as a historian, in large part, to the family stories I heard from my

grandmother as a child, I offered my students the option to explore their own family histories.1 At the time, I was finishing up a first book about my

family history—about the lives of my Black and Creek ancestors after emancipation—and the book’s major questions began as family stories.

For the final paper, some of my students researched their enslaved ancestors, others researched their slaveholding ancestors, and still others researched the house histories within their family narratives—including southern plantations and northern stops on the Underground Railroad. Most importantly, I asked students to share their experiences with one another in class. They quickly appreciated the vast disparities within the archive, the infinite absences and silences, and the uneven access that we have to our family histories—in this case, an unevenness directly created by the history and legacies of American slavery. And with the support of our small team of historians, librarians, and genealogists, even those students who started out with very little “hard” evidence came to know their ancestors in new ways. This kind of research is a deeply rewarding experience that shapes how we move through the world as descendants.

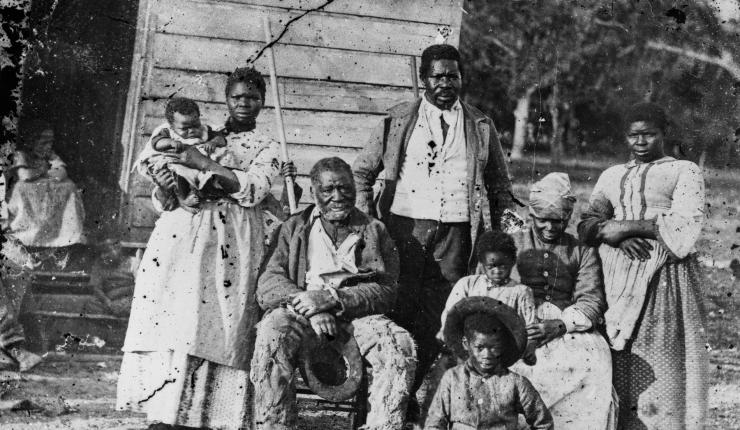

The 10 Million Names Project—an ambitious new American Ancestors undertaking—aims to harness this power for millions of descendants. The 10 million

people who were enslaved between the sixteenth century and the American Civil War within the boundaries of what became the United States have approximately forty-four million descendants living here today. And those forty-four million are more likely to encounter significant challenges tracing their ancestry. Slavery separated families and obscured family history. Before the mid-twentieth century, data about enslaved Africans and their descendants was often deliberately obscured or altered, or simply unrecorded in the first place. This lasting legacy of slavery—the erasure of family history— remains with us today. So, while those Americans attempting to claim Mayflower ancestry have had extensive records to consult, African Americans who have been collecting their family histories and genealogies for centuries have not generally had easy access to collective repositories of genealogical data. This divergence is a stark reminder of our unequal and uneven access to our familial past.

The 10 Million Names Project aims to recover names and stories of the estimated 10 million women, men, and children of African descent who were enslaved in the U.S. before 1865, through a collaborative network of expert genealogists, historians, cultural organizations, and descendant communities. It aims to establish a document-based research repository and to amplify the voices of people who have been telling their family stories for centuries.

The project’s research areas encompass the majority of sources we will use to locate these names:

- Making America: Records of Enslaved Laborers within and beyond the Plantation

- On the Battlefield: Records of Soldiers, Veterans, and Refugees

- Freedom Journeys: Records of Mariners, Migrants, and Fugitives

- Community Building: Records of Black Institutions (including especially Black churches and schools)

- Remembering Slavery: Testimonials after Emancipation

Covering three and a half centuries, the project attends to the vastly diverse origins of what later became known as “African American” or “Black” in the United States. Enslaved people of shared African and indigenous ancestry are included, as well as ancestors who were enslaved in the Caribbean before relocation to the United States.

While historians and genealogists have long known and engaged with the individual names of enslaved ancestors—or often a group of names joined by a single family or single plantation—the notion of a free and publicly available database where these names might live came as a revelation to this historian. I am accustomed, like most historians of slavery, to rifling quietly through manuscript papers and census records, hand-written family trees and family reunion records, in a process that is often solitary, singular, and sometimes sacred. But it is also a process that is relatively inaccessible to many descendants. Many face the understandably stark challenges of transcending from free to enslaved ancestors in the antebellum period—what is sometimes called the notorious “brick wall” of 1870. And yet the will to remember among African American descendants lives and grows. One need think only of the explosion of genetic genealogy and DNA tracing over the last two decades, or that one in three Black families tuned in to Henry Louis Gates’s Many Rivers to Cross: The African Americans in 2013. Nearly half a century prior, thirty million families tuned watched Alex Haley’s Roots when it aired on ABC in 1977, and tens of thousands joined the African American Historical Genealogical Society that formed later that same year.2

Had the resources, technology, and collective will existed at the time, I know this type of database project would have begun the moment Roots aired. Or, it might have begun eight decades prior, when, in his 1892 autobiography, Frederick Douglass wrote: “The reader must not expect me to say much of my family. Genealogical trees did not flourish among slaves.”3 Our ancestors were not only separated from their family members but separated, to varying degrees, from their family histories and family names.4 While descendants today continue to grapple with the deprivation of family history, we now know better than ever that names and fragments of family histories—spanning Africa, the Caribbean, and the U.S.—did circulate, hold value, and survive. In many cases, this knowledge became all the more powerful because it was denied or obscured. Douglass’s contemporary, Henry Highland Garnet—who was, like Douglass, enslaved as a child in Maryland and became a leading abolitionist of the nineteenth century—knew the name of his African-born grandfather and knew his African heritage— and carried this knowledge proudly into his work as an abolitionist and Pan Africanist.

Indeed, African and African American naming and genealogical practices were a powerful and often-veiled form of resistance and identity throughout the history of slavery—and, more broadly, African American history. I recall an interview with Adelaide Sanford, a leading educator who grew up with her formerly enslaved grandmother. Her grandmother relayed that whenever her mother could get her “quietly to herself, which was not often,” she would reiterate, “Always remember that you are an Ibo. And someday you will be an Ibo woman.” As a child, Adelaide’s grandmother was not certain what this meant, but because of how this knowledge was shared—“with whispering, with holding, with affection,”—she “kept that in her heart.”5 For many, knowing the names, origins, and life stories of one’s ancestors has been life changing. As Alex Haley wrote, “In every conceivable manner, family is link to our past, bridge to our future.”6

Today, the resources, technology, and collective will exist to recover and restore many of these names to their families and to U.S. history. In the last several decades, large historic datasets about African Americans have begun to be digitized and made available to scholars and researchers. Overseen by genealogists and historians in partnership with Black-led genealogical societies and families, the 10 Million Names Project will leverage the latest technology and resources so that data from smaller archives and libraries can be digitized. The result may be the largest database of African American names from more than 350 years, and the ability to connect these names to present-day descendants.

The digitization infrastructure and capacity to leverage cutting-edge technology—including recent advancements in optical character recognition, allowing researchers to identify names in handwritten records— will allow the project to quickly locate names in very large data sets. This project aims to use these resources to knit together the longstanding generational work of African American families, communities, and institutions. In short, the project has the potential to offer a bold and capacious response to our historically uneven and unequal access to family history in this country.

In recent years, psychologists have begun to examine the importance of a strong “intergenerational self ”: children knowing they “belong to something bigger than themselves.” One study revealed that in the face of conflict and uncertainty, “the more children know about their family’s history, the stronger their sense of control over their lives, the higher their self-esteem.”7 Such findings have powerful implications, both urgent and hopeful, for the African American experience. As the writer Ronne Hartfield has noted, “Our mother’s stories have given us the maps by which our tribe locates its journeying, its streams and rivers, its stony places, its sometimes astonishing, more often incredibly affirming twists and turns.”8

Kendra Taira Field, PhD , is the Chief Historian of the 10 Million Names Project

Kendra Taira Field, PhD , the Chief Historian of the 10 Million Names Project, is Associate Professor of History and Director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at Tufts University. She is the author of Growing Up with the Country: Family, Race, and Nation after the Civil War (Yale, 2018).

Field’s current book project, The Stories We Tell (W.W. Norton), is a history of African American genealogy from the Middle Passage to the present.

NOTES

1 See Kendra Taira Field, Growing Up with the Country: Family, Race, and Nation after the Civil War (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2018).

2 On viewership, see Bethonie Butler, “Everyone Was Talking about ‘Roots’ in 1977,” Washington Post, May 30, 2016. On the founding of AAHGS, see aahgs.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=Page.ViewPage&pageId=597.

3 Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, Written by Himself (Boston, 1892), 25.

4 Heather Andrea Williams, Help Me to Find My People: The African American Search for Family Lost in Slavery (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012).

5 Adelaide Sanford interviewed by Cathy Sandler (The HistoryMakers A2003.219), September 19, 2003, The HistoryMakers Digital Archive. Session 1, tape 2, story 4.

6 Alex Haley, “The Joy of Reunions,” Families, fall 1980.

7 R. Fivush, J. G. Bohanek, and M. Duke, “The Intergenerational Self: Subjective Perspective and Family History,” in Self Continuity: Individual and Collective

Perspectives, ed. Fabio Sani (New York: Psychology Press, 2008), 131–143.

8 Ronne Hartfield, Another Way Home: The Tangled Roots of Race in One Chicago Family (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004).