Genealogists tracked down a descendant of Elizabeth Freeman, the formerly enslaved woman whose freedom case helped end slavery in Massachusetts

By Tiana Woodard Globe Staff, Updated August 20, 2024, 5:21 p.m.

STOCKBRIDGE — Lisa Shepperson fluttered her eyelashes to stop her tears as she stood at the faded tombstone of Elizabeth Freeman on Monday morning. She patted the centuries-old tablet with her manicured hand, as if comforting a longtime friend.

Image: Lisa Shepperson stood next to the grave of her ancestor Elizabeth Freeman at the Stockbridge Cemetery. Kayla Bartkowski For The Boston Globe

It was the first time she saw the burial site of her ancestor at Stockbridge Cemetery. It was only three months ago that Shepperson found out she was a direct descendant of the formerly enslaved woman whose lawsuit for her freedom in 1781, helped propel Massachusetts to abolish slavery in the state.

Before then, she had not heard of Freeman until that unexpected call from a genealogist. But now, standing there, Shepperson said she could not help but feel a wave of joy rush “past my feet, to my heart, to my head, and out towards God.”

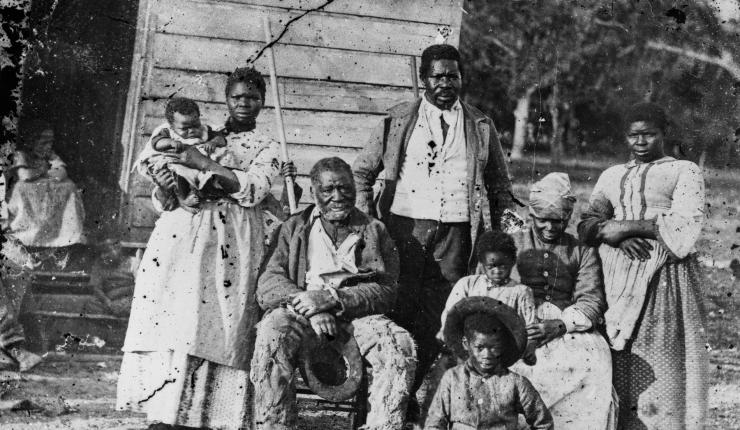

Shepperson, a Virginia-based patient service representative, came to Massachusetts last week after 10 Million Names, an American Ancestors initiative that traces enslaved people’s lineages, tracked her down and brought her to her ancestor’s home ahead of Elizabeth Freeman Day.

Each year, communities around Massachusetts celebrate Aug. 21, the day of the trial in which the jury ruled in Freeman’s favor. But there’s an air of hope surrounding the day this year.

Finding one of Freeman’s descendants felt like a miracle. Genealogical breakthroughs over the past decade have helped African American historians and genealogists build out the Freeman family tree, but sheer luck connected the final branch to Shepperson. Now, such discoveries could have an impact on reparations discussions, which have renewed in recent years across the country as people seek to address the harm inflicted over centuries on descendants of slavery.

It is unclear whether a fleshed-out family tree could mean monetary compensation for Freeman’s descendants. But knowing your family history after generations of the broken family bonds slavery caused, historians say, is repair itself.

“The fact that it is harder [to do African American genealogy] is a legacy of slavery itself,” said Kendra Field, an associate professor of history at Tufts University. “It takes more work, it takes more investment, and it’s the work of repairing those erasures and voids.”

Freeman’s life is better documented than most enslaved people of her era. Her headstone suggests she was born around 1744. Known then simply as “Bett,” she was owned by Dutch landowner Peter Hogeboom in Claverack, N.Y., during her earlier years. Then in a move that would reverberate down the years, she was moved to Massachusetts in the small town of Sheffield in the Berkshires to work under Hogeboom’s daughter, Hannah, and her husband, Colonel John Ashley, as an enslaved domestic servant.

Image: Lisa Shepperson met a descendant of Agrippa Hull, Wray Gunn, in his home in Sheffield. Agrippa Hull was a neighbor of Elizabeth Freeman. Kayla Bartkowski For The Boston Globe

In 1781, Freeman filed a freedom suit against Ashley. Theodore Sedgwick, a prominent Stockbridge lawyer, and Connecticut attorney Tapping Reeve represented her in court. Because Freeman was a woman, she couldn’t sue alone. She was joined by a man named Brom whom Ashley also enslaved.

A jury ruled in their favor. The pair won their freedom and received 30 shillings in damages. The decision was monumental; it was the first known case to successfully challenge the legality of slavery under the 1780 Massachusetts Constitution. Leaning on her precedent, Massachusetts would abolish the institution two years later, and be the only state in the Union to report no enslaved people on the 1790 federal census.

After slavery, she chose the name Elizabeth Freeman.

She started getting paid for her work, bought land, and set aside an inheritance ― impossible for most enslaved people and milestones that few then could achieve, whether in bondage or not. She worked for the Sedgwick family as a paid domestic servant and gained a reputation as a successful midwife. Freeman was one of the few free Black people who owned property in Stockbridge. And she dictated her last will and testament, which left valuable possessions to her daughter, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

“Her resilience to make sure that she was free, and what she did with her life after enslavement really stands out,” said Frances Jones-Sneed, emeritus professor of history at Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts in North Adams.

Still, despite the paper trail Freeman left behind, finding her descendants proved challenging.

Shepperson learned of her connection in May. Her mother, Margaret Baldwin, died last year, and a year later, the funeral director reached out to Shepperson with a strange message: A researcher was trying to contact her about her family history.

Reluctantly, she called Lindsay Fulton, chief research officer of the genealogy organization American Ancestors.

Skeptical, Shepperson recalled telling Fulton: “Tell me more than something that can be found in vital statistics, or we can end the call.”

Before the conversation, 10 Million Names brainstormed a list of famous enslaved people whose descendants researchers would like to find. Inspired by the 2022 unveiling of an Elizabeth Freeman statue in Sheffield, Field, of Tufts, and her colleague Kerri Greenidge, an associate professor in race, colonialism, and diaspora studies at Tufts, suggested Freeman.

Fulton and two genealogists spent months tracing Freeman’s family tree, poring over the documents she left behind, specifically her will, which listed her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren by name.

They requested birth certificates, marriage licenses, and death records. They sifted through newspaper archives and Civil War pensions. They followed the family’s lineage across state lines and into Connecticut, where they found a name: Margaret Baldwin, a woman seven generations away from Freeman.

But they got stuck there. Until Shepperson, Baldwin’s daughter, returned Fulton’s message.

“I don’t know what happened here, but for whatever reason, Lisa had enough faith to call me,” Fulton said.

Shepperson’s knowledge of her family history is limited. Her mother was born in New Haven County, Conn., and was abandoned by her birth mother from an early age. Her maternal grandfather, Freeman’s direct descendant, wasn’t present in her mom’s childhood, either, Shepperson said.

Shepperson’s mother and grandparents didn’t reunite until later in her mother’s life. But years that could’ve been spent learning where she came from, and repairing broken relationships, were already gone.

The family story “got lost in the shuffle around of people,” Shepperson said. “Nobody sat down to talk about it.”

So when Field and Greenidge revealed her ancestral connection during a Zoom call, Shepperson “didn’t even have the words.” Her voice cracked with emotion. If only her mother or grandmother knew the power they came from, she said.

“It’s the strength my mom needed,” she said. “The strength my grandmother, who gave all her kids up, didn’t have.”

It’s been a few months since Shepperson learned of her connection to Freeman. While she doesn’t yet know everything about her family’s history, she hopes her visit to Western Massachusetts will ensure future generations have the knowledge within reach.

On Monday morning, Shepperson stepped out of a black sedan and onto the green pasture that researchers determined was once Freeman’s property.

It was moving to see what Freeman had come to own, but learning about her life left Shepperson with more questions, too: How had her ancestors lost the modest parcel she stood upon? Why was the centuries-old tombstone unkept for so many years? Were the land, jewelry, and clothing Freeman bequeathed to her loved ones ever received?

But with time and intensive research, Shepperson hopes she can find some answers soon.

There is one quote in particular from Freeman that has given Shepperson newfound strength. She learned of it through a biography by Catharine Sedgwick, an author and daughter of Theodore Sedgwick, whom Freeman cared for while working for the family.

“Any time while I was a slave, if one minute’s freedom had been offered to me, and I had been told that I must die at the end of that minute, I would have taken it just to stand one minute on God’s earth a free woman,” Sedgwick wrote Freeman saying.

Shepperson taped a copy of the quote on her work computer.

This story was produced by the Globe’s Money, Power, Inequality team, which covers the racial wealth gap in Greater Boston. You can sign up for the newsletter here.