For the first time, genealogists have identified a living descendant of Elizabeth Freeman, the first African American woman to win a lawsuit for her freedom in Massachusetts

By Aaron Simon Gross, The Berkshire Eagle, August 24, 2024

SHEFFIELD — Just four months ago, Lisa Shepperson had never heard of Elizabeth Freeman. But this spring, she learned that Freeman was not only her ancestor, but the first African American woman in Massachusetts to successfully file a lawsuit for her freedom. What’s more, Shepperson learned that she was Freeman's first living descendant who genealogists and historians had been able to identify.

“I am standing here, the ninth generation of Elizabeth Freeman, with graciousness and humbleness,” Shepperson said Wednesday morning from the grounds of Ashley House, where Freeman was enslaved. It's also the location, where Freeman overheard Col. John Ashley and other prominent men discussing the 1780 Massachusetts Constitution — that declared "all men are born free and equal" — which started her pursuit of freedom.

Shepperson, 58, traveled from Virginia to the Berkshires for Elizabeth Freeman Day. Her trip included visits to the Stockbridge Cemetery, where Freeman is buried in the adjacent Sedgwick Family Cemetery; Great Barrington Town Hall, where Freeman litigated her case; land owned by Freeman, which was near Agrippa Hull's homestead, and Sheffield’s Elizabeth Freeman Monument.

Lisa Shepperson, Elizabeth Freeman’s living descendant, visits Elizabeth Freeman’s grave in the Sedgwick Family Cemetery, also known as the Sedgwick Pie, adjacent to Stockbridge Cemetery.

“This week was a whirlwind. We were here, there and everywhere," she said. "This is all information that’s new for me, as well, but I’m learning. It's been so emotional. I knew nothing of Grandmother Freeman. Nothing.”

That changed a few months ago, on a Zoom call with historians Kendra Field and Kerri Greenidge, who are a part of 10 Million Names, a project from the nonprofit organization American Ancestors.

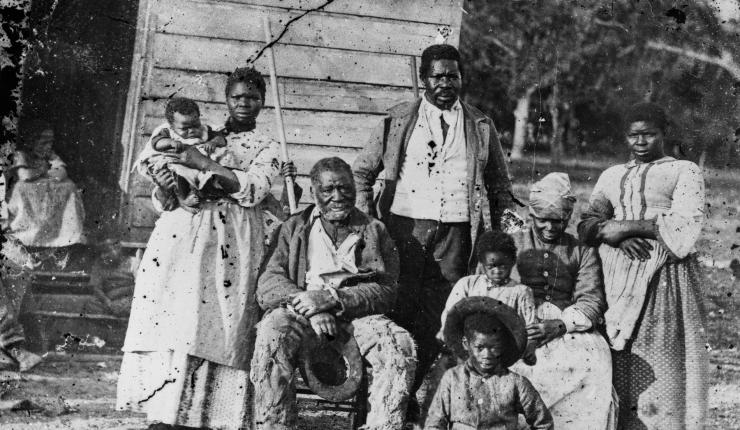

“The mission is to document the names of the 10 million people who were enslaved in the land that became the U.S. between the 1520s and 1865,” said Field, the project’s chief historian. “That’s incredibly important, but also very difficult work. It’s a generational project, and it'll take many years to get to the point where we flesh out the database.”

For 10 Million Names, historians work alongside genealogists.

"Those two groups don't often overlap," Greenidge said. "Historians tend to start with ancestors and move forward. Typically, genealogists begin in the present day and make their way back.

Image: Lisa Shepperson gets a selfie taken with professors Kendra Field and Kerri Greenidge, historians from Tufts University who spearheaded the project that discovered that she was the descendant of Elizabeth Freeman.

When researching African American history, however, genealogists often come up against what’s known as “The 1870 Brick Wall,” from the first federal census that included newly emancipated people.

"A lot of time, people will get to that point and have difficulty getting to the point of enslavement," said Lindsay Fulton, the genealogist who worked on this project. "And people have been looking for Elizabeth Freeman descendants for some time now.”

Freeman left behind a detailed record, including a will stating relationships to her grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Fulton, along with Field and Greenidge, took that as their starting point.

From there, they looked at birth, marriage and death records, as well as census records.

"You use historical newspapers and go into archives that genealogists might not go into like the Massachusetts Historical Society," Greenidge said.

That led to a descendant who served in Connecticut’s first African American regiment in the Civil War, and had a detailed pension record.

Fulton asked a Connecticut-based genealogist to go to a town clerk and the state archives to look more into that man and his descendants. Eventually, that led the trio to Shepperson’s mother, Margaret Baldwin.

“We just started Googling to see if we could get a hit on Margaret,” Fulton said. On a funeral home website, they learned that she died the previous year. “So we called and said, ‘We know you probably have next of kin. We understand this is really strange, but can you give them our phone number?’”

Shepperson got the message from the funeral home and was skeptical.

“I was leery because people are scammers and they do a lot of things with people’s information, anybody can find anything,” she said. But when she got on the call with the team, and learned about her ancestor, any fears were assuaged.

“I was bawling, crying, crying, crying. I couldn’t stop crying, so excited, so blessed to be a part of it," Shepperson said.

And she's still metabolizing what it means to be a part of that legacy.

“Elizabeth Freeman's suit set the precedent for the end of slavery in this region," Field said. "So the story of her life, her resistance to the violence of slave ownership that she endured and her protection of her family, her daughter, her commitment to her own emancipation that led to the emancipation of many others is really a tremendous moment in American history."

Not every connection that these historians and genealogists make will involve a figure as prominent as Freeman.

“This is one story of, well, 10 million, and the 10 million ancestors have 44 million descendants approximately," Field said. "There will also be many other stories where we’re just thankful to have any name at all. The vast majority will not be household names, but their stories matter nonetheless."

Before leaving the Berkshires, Shepperson visited Freeman's gravestone one more time, leaving a bracelet and kissing the headstone. When she's at the grave, Shepperson is consumed by thoughts of her mother.

“She’s just smiling. We made it, mommy. Here we are," Shepperson said. “I feel so connected. My mom always rests with me — I can hear her in my ear. But now I can hear Grandmother Freeman saying that the job isn’t finished. We still have to make sure that everybody will come together to acknowledge and accept who she is.”